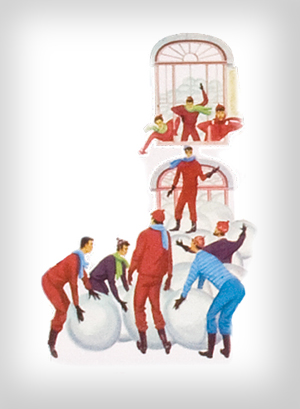

The campus groundskeeper stood at the top floor of the administration building and looked out the window. The building sat in the middle of the college, which gave him a wonderful view of the beautiful campus he maintained. It was Spring, and he had laid new green turf throughout the grounds. The campus design was simple: stately red brick buildings surrounding a wide expanse of open space, which was laid out as a grid of grass and sidewalks. Students could travel North or South, or East or West, with ease.

And then he saw it. At first, he wasn’t sure it was real. Perhaps it was a streak in the glass of the window, or a mirage of some sort. Once he realized that it was truly what he thought it was, he dropped his cup of coffee on the ground. He looked closer, and then began to look more closely all around. Soon he realized that they were everywhere! His lovely campus was being ruined! Those damn lazy students were cutting diagonal lines through the grass, leaving brown dirt paths in the middle of his lovely green turf.

“Use the sidewalks!” he shouted to no one in particular but the window. He immediately placed a call to his crew, and they placed new sod, seed, and fences up so that the grass would grow back over the paths. A month later, he removed the fences, hoping that they had made the point. “The students will not win!” he thought. An hour later, students began cutting diagonally through the grass and the dirt paths reemerged. The groundskeeper gave up. He was close to retirement and sadly lamented what he saw as the ugly campus grounds until the day he left.

A new groundskeeper was hired, and one day was standing in the same place the retired groundskeeper had once stood, looking out upon the campus. He too noticed the dirt paths that had been worn into the ground, but he didn’t see them as ugly or intrusive. He also placed a phone call in response.

A month later, the brown dirt paths had been covered by sidewalks.

Is cutting across a lawn instead of using the sidewalk an act of defiance? Not really. But the story does provide a fairly good analogy for how we – as professionals that work with college students – view their actions and decisions. Administrators often believe that they have laid out the best path for students, and are perplexed when a different path is chosen. Administrators then stand their ground, channel their deepest Dean Wormer, and try to put the students back on the “correct” path.

And the students, innocently free from notions of bureaucracy, legislation, rules, and legalities, calmly say in return: “Uhh, I see the sidewalks you laid out for me, but it’s a lot faster to go this way.”

And administrators have a choice in this moment, just like the groundskeepers in the story above. Way too often, the choice we make is to ignore the students, stick to the sidewalks we have created, and stubbornly demand they use them.

This is our usual response to the defiance and/or rebelliousness of our students. What if the next time you were faced with that choice, you took a deep breath, swallowed a little pride, and said, “Maybe the students are on to something.”

Years ago, fans at Duke basketball games had the reputation of being mean and nasty to opposing teams and fans. Embarrassingly so. The university president was faced with a choice: use his power and authority to squash this problem, or, find a way to embrace it. Whereas 99% of administrators in his position would have fired off a tersely-worded letter or statement that condemned the acts and laid out a terrifying set of consequences for anyone who acted out, Terry Sanford (or Uncle Terry as he was called) instead wrote a different kind of letter. He celebrated the enthusiasm of the fans, and asked them to channel it into a force for good:

"I don't think we need to be crude and obscene to be effectively enthusiastic. We can cheer and taunt with style: that should be the Duke trademark."The results are infamous. The Cameron Crazies at Duke are now known for their very tenacious yet polite cheers. For instance, when a referee misses a call, the preferred chant is "We beg to differ!"

"I suggest that we change. Talk this matter over in your various residential houses. Think of something clever but clean, devastating but decent, mean but wholesome, witty and forceful but G-rated for television, and try it at the next game."

Another example. When I was a senior at Miami in 1998, there was a “riot” of students in the center of town late one night. I don’t remember what sparked it, but eventually hundreds of students took to the streets to party, cause damage, and be obnoxious. A year later, the anniversary of this event was approaching and there were rumors of a second riot. A moment of choice. Most universities would have imposed some draconian rules on alcohol or parties, doubled the police presence, and had suspensions ready to hand out as quickly as candy at a parade. Miami made a different choice. They invited a core group of students to design and carry out an outdoor rally and festival to be held on the anniversary night at the site of the riot. There were bands and activities. The streets were full of students who had left the bars and found something pretty cool waiting outside. The Red Brick Rally became an annual tradition.

In each of these examples, the administrators noticed something in the students – a spirit that they wanted to put to a productive use. They saw the dirt paths coming, and put usable sidewalks in their place.

So, how do we celebrate and use the defiance that’s in the DNA of our fraternities and sororities?

First, we can put students in a position to use that defiant spirit for good. Let's pledge to stop using students on committees or task forces simply as tokens. Let's give them significant work, like crafting policy and strategic plans. When they vocally disagree with an idea, let’s resist the inclination to think “they just don’t understand,” and instead think “maybe we just don’t understand.”

We can also encourage grassroots movements. There are students all over our campuses that send signals of rebellion, but their passions never get off the ground. The next student who volunteers his/her disdain for hazing should be encouraged to move their conviction to action. The next student that asks you what you're doing about the poor fraternity grade report should be answered with, "I've been waiting for you."

We can be willing to be wrong. To be honest, now that I have stepped away from campus work for a while, I look back at some of the policies I treated as gospel and I laugh. Now, I wish I had handed them over to the student leaders I advised and gave them the chance to rewrite them so they worked better. I recently consulted with a university in which a major battle of wills had erupted between the IFC and the university staff over an event authorization process. Is that worth a major battle? An event authorization process? Sometimes we are wrong and we need to happily admit it. Sometimes we are right, but that shouldn't make us inflexible.

Finally, we can simply and calmly accept this defiant spirit for what it is - an inherent trait that breathes life into fraternities and sororities. It can give us headaches and heartburn. It can also make our work less efficient and messier. But, it also keeps us accountable. It encourages innovation. It can make life more playful and spirited. It can help those of us who have allowed policies, rules, regulations, and bureaucracy to rule our work remember that we shouldn't take those things too seriously.

It may even make us radically change the way we do our work. But that's okay.

After all, we may just have defiance in our DNA as well.